Is it possible to develop and implement a regional certification program for ATVET teachers in Central America? This question, posed at a workshop at EARTH University conducted by Henry Quesada and John Ignosh in April 2017, raises concerns about the value of professional development for agricultural educators in Central America. Teachers and administrators are working to bridge the gap in updating technical and pedagogical skills, emphasizing the importance and value of continuing education to their governments’ Ministries of Education and Agriculture. The workshop participants concluded that there is a need for regional ATVET programs. At the InnovATE symposium, Quesada, Ignosh and Anny González (of the Central American Educational and Cultural Coordination (CECC) of the Central American Integration System (SICA)) presented the findings and proposed pathways to create ATVET programs for educators that are specific to challenges and opportunities for growth.

Dr. Henry Quesada speaks during his session about capacity building for Technical Vocational Education and Training Programs (TVET) pictured above.

ATVET stands for Agricultural Technical and Vocational Education and Training (ATVET). The educational process involves, in addition to general education, the study of technologies and related sciences, and the acquisition of practical skills, attitudes, understanding and knowledge relating to occupations in agriculture.

The question proposed raised concerns not only about teachers’ education in Central America, but the discussion generated after the presentation shifted to compare international examples of how continuing education is perceived and taught regionally even with national standards. I found the discussion particularly interesting, when one discussant compared and contrasted the countries outside Central America that have national standards of education, and teachers across different regions teach the educational materials differently. The problem is the installation capacity through large areas and regions of land because of cultural differences among those regions and people, leading to those differences in teaching. Following that are the issues with national standards for education. Agricultural education has more barriers to pass between national and regional standards because agricultural environments differ in every bio-region. Therefore, national standards can become outdated when focus is diverted from regional growth and opportunities catered to specific problems, to a general, larger national issue.

Before the EARTH workshop, a pre-event survey was used to gather more information about the participants themselves (approximately 35 invitees) comprised of ATVET instructors and administrators, ministry of education and agriculture representatives, and university and NGO partners from Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. Out of 19 responses, more than 33% agreed that TVET training and professional development are frequently offered, and the cost of attending them are low. However, less than 33% agreed that the quality of these programs was high. During the workshop, attendees were asked if there is a need for a regional program for training and certification of educators in TVET, and the feedback from all the focus groups were positive indicating that there is a need for regional programs. So, it is safe to assume that while there are workshops available, there is a demand for regional programs more specific to their economic and environmental challenges.

Programs like the ATVET teacher certificate program are critical to develop teacher value and an importance in education training, as well as education in general. The Central American Educational and Cultural Coordination (CECC) is a Technical Secretariat of the Central American Integration System (SICA). It is working across borders to structure and guide programs in ATVET, facilitating communication and information between government authorities. In areas where educators do not have access to discussion and sharing with other educators and authorities, education is not seen as important and therefore undervalued. This view is detrimental to not only those teachers but to the youth. It undermines education systems because of the inherent institutional crack that trickles down to the students. In addition, ATVET programs in agriculture and agroforestry education are a critical economic driver in developing countries. When agricultural education expands, agricultural production increases in yield, trade, and profit, poverty decreases, food security increases, and education becomes valued as a long term investment. Therefore, ATVET programs should be considered a public good. The public is getting benefits from the educators becoming better in their practice.

Thus, from the presentation, potential pathways to follow are to create opportunities to exchange ideas using face-to-face and online platforms, focus on training and development first, leverage on installed capacity, use success with local evaluation, and meet with CECC-SICA every 6 months as a forum to get support for a regional certificate program. I also believe that building a network with a solid foundation of educators, institutions, and government organizations is a means for increased communication across sectors. All of these pathways to capacity building for TVET programs can ultimately lead to an increase in government and non-government support and creating more value to agriculture education.

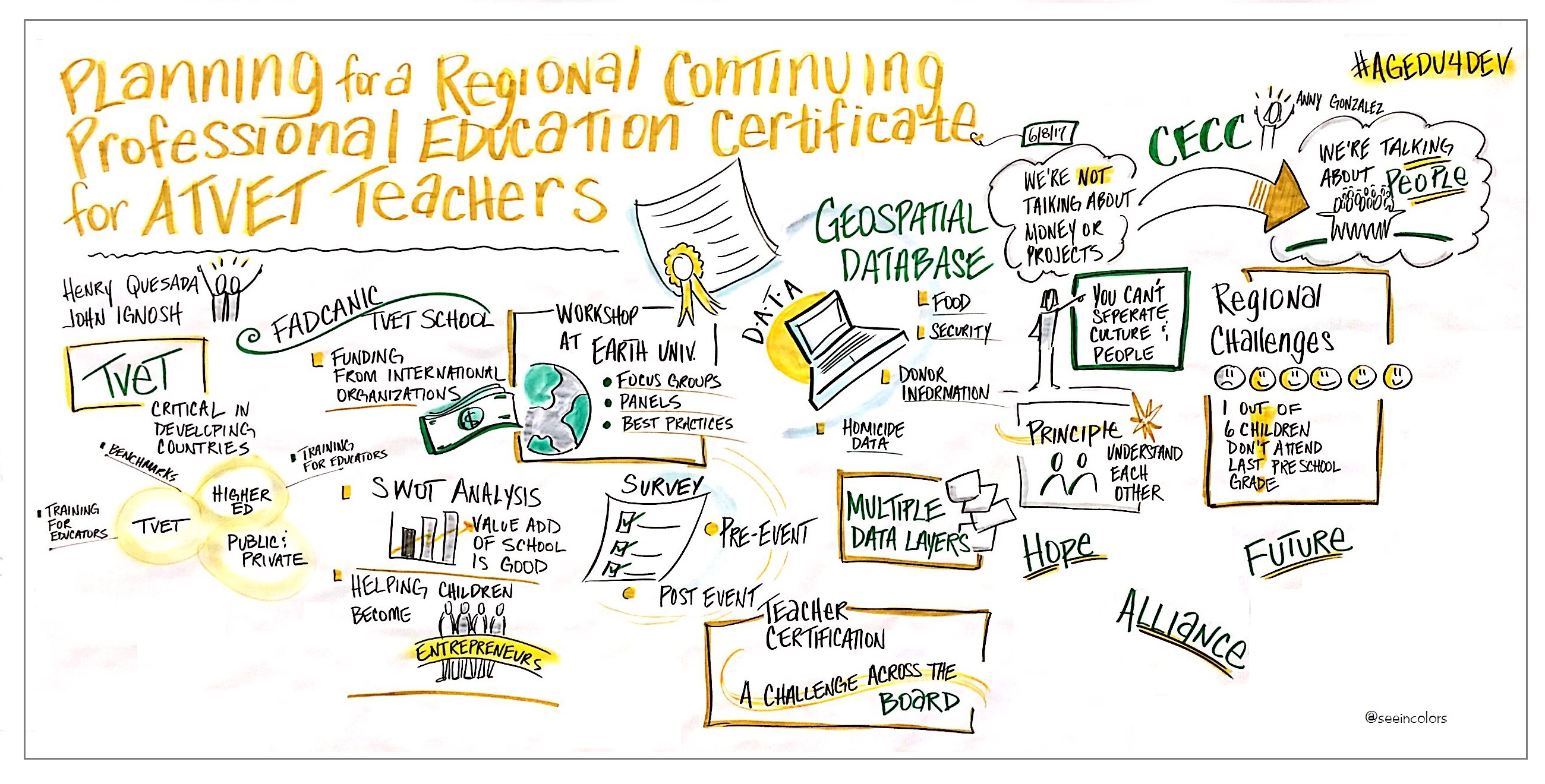

A visual summary made by Lisa Nelson from See in Colors during the session.

Ellen Huber is an undergraduate student at Virginia Tech, majoring in Environmental Science. She is a research assistant for the USAID-funded Innovation for Agricultural Training and Education (InnovATE) project.